Capitalist Realism: The only theory therapists (unconsciously) use to understand economic relationships

Part 2 in a series examining labor exploitation in the mental health industry

This is part 2 in a series trying to understand whether psychotherapy group practice owners are exploiting pre-licensed associates. Read part 1 here.

Mark Fisher was obsessed with mental health issues as political rather than individual phenomena. In 2014 he wrote:

Writing about one’s own depression is difficult. Depression is partly constituted by a sneering ‘inner’ voice which accuses you of self-indulgence – you aren’t depressed, you’re just feeling sorry for yourself, pull yourself together – and this voice is liable to be triggered by going public about the condition. Of course, this voice isn’t an ‘inner’ voice at all – it is the internalised expression of actual social forces, some of which have a vested interest in denying any connection between depression and politics.

Fisher was one of very few people writing about how if there are observable increases in markers of human suffering in a society – depression, suicides, drug addiction, PTSD, and so on – then we should look at what’s going on in society and change that instead of only ever throwing individualized “treatments” at individuals (ie, psychotherapy, psych meds).

Everyone has their opinions about what’s making society terrible, but Fisher believed it was primarily neoliberal capitalism. People often just call it “neoliberalism.”

What in the hell is “neoliberal capitalism”?

(If you already know what neoliberalism is, scroll down to the capitalist realism section.)

You may remember during the 2016 U.S. election era when “Bernie Bros” were hurling the epithet “neoliberal” at anyone who supported Hillary Clinton. It was meant to be mean, and if it were translated into corny therapy-talk it might look like this:

“It deeply hurts me knowing that you only superficially support social progress while also supporting the neoliberal form of capitalism we’re currently living in, which I believe to be the ultimate cause of modern social injustice.”

But Bernie Bros weren’t the only ones concerned with neoliberalism. A small handful of mental health professionals have actually written a bit about it.

If you’re a fan of the now popular therapy modality Internal Family Systems, you may be familiar with Richard Schwartz and his 2021 book No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model. He writes in the introductory section:

We need a new paradigm that convincingly shows that humanity is inherently good and thoroughly interconnected…Such a change won’t be easy. Too many of our basic institutions are based on the dark view. Take, for example, neoliberalism, the economic philosophy of Milton Friedman that undergirds the kind of cutthroat capitalism that has dominated many countries, including the US, since the days of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. Neoliberalism is based on the belief that people are basically selfish and, therefore, it’s everyone for themselves in a survival-of-the-fittest world. The government needs to get out of the way so the fittest can not only help us survive, but thrive. This economic philosophy has resulted in massive inequality as well as the disconnection and polarization among people that we experience so dramatically today. The time has come for a new view of human nature that releases the collaboration and caring that lives in our hearts.

Psychiatrist Anna Zeira published an exhaustively comprehensive piece in the Community Mental Health journal in 2022, titled Mental Health challenges Related to Neoliberal Capitalism In The United States. Highly recommended in its entirety.

Zeira correctly assumes most mental health professionals have no idea what neoliberalism is, so she breaks down what neoliberal policies were starting in the 1980s:

Corporate tax breaks and incentives

Deregulation of big business and banks

Introduction of practices that strongly favor employers over unions;

Transferring resources from public ownership to contracted out private sector services

Drastic budget cuts to public sector

Elimination of various social programs

Deregulation of foreign investment rules for global 'trade liberalization' leading to more international trade

Outsourcing manufacturing jobs overseas for the cheapest labor possible

Increase in government surveillance, policing, mass incarceration to deal with increases in poverty, crime, behavioral problems in society

She delineates the various impacts neoliberal policies had on the U.S. population:

Massive, unprecedented widening of gap between rich and poor

Poorer people got less access to social services provided by government

Privatization of social services created massive nonprofit complex competing for smaller pool of government funding, increasingly reliant on foundations established by the rich

Nonprofits increasingly became more businesslike (ie, hospitals and universities)

Unions became weaker in capacity for bargaining power with employers, less politically influential

Working conditions worsened in the U.S. due to weakening of union power

Lower wages for blue collar workers because they were now competing with cheaper labor overseas

Rise in cost of living required low wage workers to have multiple jobs (ie, side hustles)

U.S. becomes most populated prison system in the world

Neoliberalism made everyone hate themselves more

“Additionally, economic and social policies created a change in ideology favoring individualism, materialism, and competitiveness, which are not compatible with human needs such as social connection and community, leading to anxiety and depression (James, 2008).” — Anna Zeira

Zeira also uses a mountain of citations and references to show how the neoliberal turn impacted people’s mental health. Read the article for yourself to get into the weeds, but for our purposes one major impact was what neoliberalism did to our way of thinking. Our theoretical orientation toward ourselves, our relationships, entertainment, economics, politics, culture — the whole world.

If the beginning of neoliberalism officially began due to policy changes in the 1980s, then the next enormous blow to the collective American psyche was the collapse of the USSR which came right around the corner.

Capitalist Realism: the ideology we all adopted after the collapse of the USSR

The collapse of the USSR from 1989-1992 was an important world event that in the 2020s we don’t think about much, although it still effects us invisibly.

When Mark Fisher wrote his book Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? in 2009, he thought people’s ability to dream of something better largely died with the USSR. With no alternative to capitalism, after decades of hope that there may be something better around the corner, this left everyone in capitalist societies with a kind of dullness of imagination.

A collective depressive, nihilistic mood everyone felt was an individual experience.

The term capitalist realism is an overt reference to a propaganda art movement from the USSR called socialist realism. It was state propaganda in the sense that the Soviet government required all cultural production within the new socialist society to project out a hopeful portrayal of the class based struggle between the working class and capitalist class around the world.

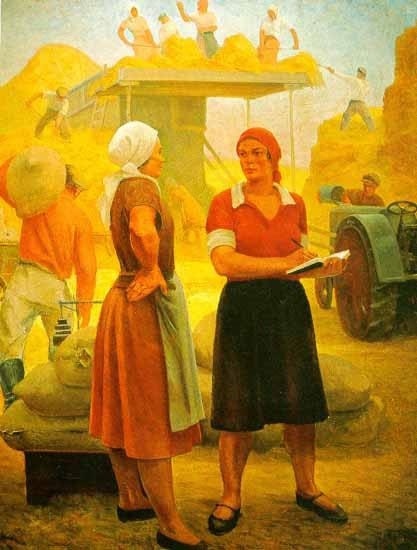

Here is an example of socialist realism art:

It was to speak to ordinary people and their lived experiences. Here is another example:

And another:

The art was to portray working people in a dignified light, showing that normal working people were the heroes of history. The propaganda side of it was that it was to portray strictly positive experiences of working people in the emerging socialist states.

Working people of the world were to look at socialist realism art and feel that they were the protagonists of history driving it forward, and that the socialist governments emerging through the 20th century were vehicles for the working class to build that better world. Everyone was to be inspired to join the revolution, co-create the better world together.

There’s an obvious dark side to this — negative portrayals were banned by the government. Cultural production didn’t capture anything about starvation, illness, violence, corruption, or anything else going on in the USSR that would paint new socialist states in a bad light.

It was the USSR trying to do PR spin and marketing so everyone would like the brand of socialism without critique. Not dissimilar to Nike never making ads about children in sweatshops making their shoes, or Frosted Flakes never telling parents that that their cereal is poisoning their kids.

The mood of socialist realism was intensely optimistic about the present and the future, even if it was a forced kind of optimism. It was stoking the world’s imagination about the possibility of everyone’s needs being met, standards of living only increasing, work eventually becoming automated so people could have more free time, colonizing space, flying cars, etc.

When the USSR collapsed, there was no more forced optimism about the future emanating from socialist states.

Instead of the capitalist West erupting into celebration of true freedom finally being achieved, it was observably left with more of a hopeless, depressive mood. Neoliberalism was setting in, which meant unions were dying, government programs were dying, unemployment and crime was rising, mass incarceration was rising.

And no capitalist state passed down formal edicts to its sites of cultural production (ie, Hollywood) to overtly brainwash working people that things were better than ever — the capitalist state just let Hollywood do whatever was popular and therefore profitable. What became popular was nothing like socialist realism — more like the opposite.

“It is easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism.”

Fisher found that from the 1990s to the late 2000s that popular capitalist cultural production about the future was mostly very depressing and terrifying dystopian fiction about the world ending.

Simultaneously, cultural production in the form of advertising had a subtler propagandistic edge that works on the unconscious. You’re an individual, individualism is the thing. You’re a consumer, forget about being a worker who’s squeezed by a capitalist. Don’t try to understand what this system is, how it works, how it got like this — there is no history, there is no future.

Be here now.

This moment is it.

Reality is yours to create.

You’re in control.

You’re uniquely special — more than anyone else.

Now buy this stupid fucking thing nobody needs and tell everyone you know to buy it too.

Socialist realism was honest about having an ideology

Socialist realism was very honest about what it was doing. It was pushing ideology. What’s ideology? A theoretical orientation toward the world, society, politics, economics, culture. It’s how you explain to yourself why and how the world works the way it does, and most importantly how the world SHOULD BE.

Ideology is concerned with the future.

Ideology commits you to a long term project.

Socialist realism was pushing a specific ideology called Marxist-Leninism. The Maoist period in China was pushing Marxist-Leninism-Maoism. (I know, it gets weirder the more you learn about socialist history.)

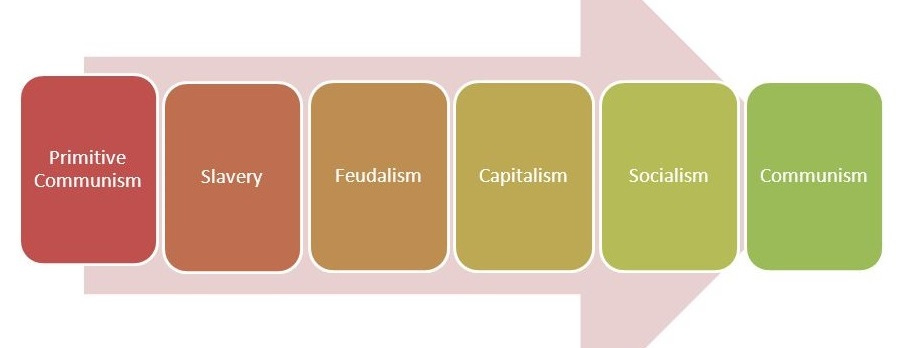

Ultra-simplified, Marxist-Leninism wanted to inspire a glorious global revolution where working people fight to govern their own societies and economics instead of being ruled by plantation owners (slavery) or royal families (feudalism) or the 1 percent (capitalism).

Socialism would be a transitional stage between capitalism and a future society called communism. Thus, communist parties were naming the eventual future — perhaps in hundreds of years into the future — they wished to usher in through a transitional stage called socialism, which could only be facilitated through a “worker’s state.”

(Much of this comes from Marx’s theory of historical materialism which we’ll explore more later.)

The point of this is not to sell you Marxist-Leninism as an ideology (unless that’s your thing) — we’re just looking at a conceptual framework of understanding capitalism and history and economics and politics that came from a specific period of history and part of the world, long before neoliberalism became the air we breathe.

Capitalism pretends to be non-ideological

I’ve had many atheist and agnostic clients who say something like “I wish I could be religious because religious people feel like they have it all figured out.”

Ideology whether it’s political, religious or otherwise, gives you some grounded framework of understanding reality. It motivates you. Gives you meaning and purpose. (Makes you less depressed?)

If you have no ideology, no belief about how things are or should be, you’re floating around in confusion and dissociation. What’s the point? Who cares? Who knows?

Fisher borrows from philosopher Slavoj Žižek to make a point about capitalism’s fake non-ideological position:

”…today's society must appear post-ideological: the prevailing ideology is that of cynicism; people no longer believe in ideological truth; they do not take ideological propositions seriously. The fundamental level of ideology, however, is not of an illusion masking the real state of things but that of an (unconscious) fantasy structuring our social reality itself. And at this level, we are of course far from being a post-ideological society. Cynical distance is just one way ... to blind ourselves to the structural power of ideological fantasy: even if we do not take things seriously, even if we keep an ironical distance, we are still doing them.”

Mark Fisher wrote about capitalist realism as a form of collective depression. It makes everyone hopeless about the future, fatigued from all the consumerist messaging everywhere, self-loathing from not being rich enough or smart enough or sexy enough or light skinned enough or tall enough or or or or or—

Invisibly, capitalist realism therefore blankets all of us into a bad mood, dulls our imagination, makes us hopeless, tells us we’re helpless, and makes us blame ourselves for how we’re all feeling.

And it keeps capitalism intact, no matter

what

we

do.

Capitalist realism as a form of collective depression

There are two very specific aspects of capitalist realism that make it a sort of collective mental health diagnosis. Reflexive impotence and depressive hedonia.

Reflexive impotence and depressive hedonia

Reflexive impotence superficially refers to our collective and automatic inability to change capitalism once we’ve concluded there’s something wrong with it. Psychodynamically, impotence has to do with our low ‘libininal energy,’ or motivational drive. We mostly don’t actually give a shit (looking like a bunch of limp dicks), and when we do, the best we can do with this impotent energy is something totally ineffective such as share our negative attitudes about capitalism somewhere, usually online.

This reflexive impotence phenomenon is a ritualistic behavior that those who “oppose capitalism” engage in as a cope to defend against feelings of hopelessness and powerlessness, since nobody actually thinks there’s any serious strategy or political commitment that could get us out of the nightmare. Instead, engaging in constant disavowal and denunciation of capitalism, or some situation or mechanism within capitalism, is all most of us do. Because what else could we do?

Here is one of infinite examples of this effective, denunciative behavior:

And here’s Fisher leaning into Zizek again:

“Capitalist ideology in general, Zizek maintains, consists precisely in the overvaluing of belief - in the sense of inner subjective attitude - at the expense of the beliefs we exhibit and externalize in our behavior. So long as we believe (in our hearts) that capitalism is bad, we are free to continue to participate in capitalist exchange. According to Zizek, capitalism in general relies on this structure of disavowal. We believe that money is only a meaningless token of no intrinsic worth, yet we act as if it has a holy value. Moreover, this behavior precisely depends upon the prior disavowal - we are able to fetishize money in our actions only because we have already taken an ironic distance towards money in our heads.”

Last week, a friend and I saw a Cybertruck driving by and the friend starting making fun of it, and making fun of Elon Musk. This is another subtle example of reflexive impotence. All we can do is mock billionaires and their stupid little pet projects, because we don’t believe there’s anything we can do but denounce the bad thing. Through denunciation we exercise freedom of expression, we vent, and we admit to ourselves and others that we have no idea what to do but disavow the air we breath.

Depressive hedonia is a contradictory position where instead of anhedonia — the inability to feel any pleasure — the people depressed from capitalist realism are constantly seeking pleasure to defend against feeling so utterly hopeless and powerless to change the massive terribleness of the system they’re in. Reality for us is just too much: we’re all becoming more poor but the rich are getting more rich, climate change seems unstoppable, our devices are made from child slavery, military violence somewhere is horrible — reality is an endless downer that we have to look away from.

We need constant “hits” of entertainment and stimulation to feel better, which also exhausts us and removes us from reality, distancing us from effective strategies that might actually improve reality.

Especially for those who “oppose capitalism,” the combination of reflexive impotence and depressive hedonia equate to political immobilization. Thousands of people spending all their leisure time getting into intense political debates online, reposting “hot takes” that denounce Cybertrucks and terrible billionaires and politicians, do nothing to redistribute wealth, strengthen unions, or in any way revert neoliberal capitalism back to a more social democratic form. It is all political impotence by people addicted to the dopamine rush of getting notifications on apps built by capitalists who sell their data to further solidify the power of capitalist realism on all our psyches.

All These Crazy People Just Need Therapy, Right?

Finally, since capitalist realism tells everyone their suffering is an individual phenomenon, millions of people go to therapy to address their issues. Therapy is immensely helpful, but it is not helpful in developing a better political economic future for everyone. There is a reason that almost everyone coming to therapy is not also flocking to join political organizations and dedicating as many months or years that they do to therapy, to long-term strategies that would reduce everyone’s suffering.

And this is capitalist realism in nutshell!

What The Fuck Does This Have To Do With Group Practices?

At the end of Part 1, I claimed that the only theoretical framework therapists have to understand economic relationships and systems is capitalist realism. Here’s what I mean in context of the group practice and labor exploitation conversation.

Everyone who thinks group practice owners are being greedy or exploitative is engaged in reflexive impotence. If anyone who was appalled by said exploitation really cared, why isn’t anyone doing anything about it? Associates are not organizing together, and licensed therapists still raw about their exploitation aren’t trying to build some alternative to address the problem. Probably because nobody who cares thinks there is anything to be done — except to denounce the situation.

Everyone who thinks exploitation is being exaggerated but feels bad that associates have to live in relative poverty for five years after grad school is also doing reflexive impotence. Either “that’s just how it is” or “there’s nothing we can do about it anyway,” or some combination.

Any therapist who takes the position that the 10:000:1 ratio is bad but 2:1 is not bad — are these therapists doing anything about it? I’d love to know if so, but am doubtful.

Notice how no matter what position you take on this ethical matter, capitalist realism is informing your thinking, your feelings, your behavior. You don’t think there’s a way out. It’s all a cope for feeling hopeless about the future.

What would be a better political economic future (for therapists and everyone else)?

Part 3 is going to be all about socialism. By socialism I don’t mean evil governments ruining lives. I mean what has been theorized to be the next and better system that comes after capitalism, and the various contending ways that people conceptualize that world will be like and what need to do to build that world together.

The graphic above, shared now for a second time, is a pretty vulgar and imperfect summary of Marx’s conceptualization of human history in regard to economic modes of production driven by conflicts between the haves and have-nots. There are some aspects to that graphic that are empirically false — there is less linearity to historical development than this graphic implies, and you can have slavery and capitalism at the same time (ie, historically, America). Technically, the USSR tried jumping from feudalism to socialism without even going through capitalism. But the graphic shows simply that it’s possible that capitalism is just one political economic system that was born and will die. Maybe socialism is not the right word for what will come next. Maybe something far worse will come next. Maybe the utopian “stateless, classless, moneyless society” of communism will never come at any point in the future, and maybe the concept itself is dangerous or delusional.

It’s possible that all the dystopian fiction of the 21st century is right: capitalism will be the last system, it will collapse, and we’ll all be running around eating each other like Zombies, then humanity will go extinct. But if this is true, then let’s just stay within capitalist realism. There’s nothing we need to do but ride the ship ‘til it sinks.

In any case, socialism is in spirit the movement that emerged within earlier stages of capitalism that imagined a better political economic future than what capitalism was offering. Some socialists were geniuses, some were idiots, some were saints, some were psychopaths. We know that Stalin killed people in gulags, and Mao got people to burn professors alive for going against the party. Some people reading this have family members who fled socialist countries because of terrible things happening. But then, we also call European countries that have universal healthcare and tuition free college “socialist.” We call Canada’s healthcare system “socialist.” And of course, Bernie Sanders and The Squad are called “democratic socialists.” What does all this even mean?

Most therapists, in my experience, don’t spend a lot of time reading or thinking about this stuff. But since I’m really weird, this is kind of my whole life outside seeing clients and writing progress notes.

My hope for Part 3 is for therapists reading to be able to break through capitalist realism and be able to think more optimistically about the future. If there are better ways for the political economic system to be, then what things should we as therapists do today? How would we run group practices? What would we aim to do if we organized together as therapists to transform society outside of the therapy room?

Read Part 3 here.

Thank you for this. I do think that there is a function to the social media posting, which is to raise awareness and reach people and hopefully convert their thinking. But then it has to be taken to the next level, into real direct action.

Really helpful survey of these ideas! Not easy to summarise so many ideas this clearly. Love how you're applying these theories to such a concrete situation. Look forward to the next one :)