As a reminder, this is part 4 of a series. Quick summary:

Part 1: We looked at whether psychotherapy group practice owners are exploiting pre-licensed (and licensed) employees. I made the claim that there’s no meaningful way for therapists to properly conceptualize the issue because they only have one theoretical orientation to understand economic relationships: capitalist realism.

Part 2: This part exhaustively explained what capitalist realism is. Where the concept came from, partly from the USSR’s socialist realism followed by the simultaneous emergence of neoliberal capitalism throughout the West and the collapse of the USSR. Near the end I said the only way out of capitalist realism is to begin studying socialist theory and history, since it’s over 100 years of thought and action that run counter to capitalist realism.

Part 3: Historical materialism. The stagelike theory Marx and Engels laid out, stating that economic modes of production evolve over time within human societies, with feudalism having been born and then died, capitalism evolving out of feudalism, and at least theoretically, socialism being the next mode of production after capitalism. I did my best to make this set of ideas therapist-friendly by starting with Erik Erikson’s psychosocial theory of individual human development, then launching into Marx’s theory of economic-social development immediately after.

So what’s part 4 about?

Dialectical Materialism: The Engine That Moves Historical Materialism Through Time

The following graphic explains so much in our society and it’s something most therapists have likely never seen. I’ll explain it in words, but you can also just examine it and will probably understand it yourself.

Before getting into what this crazy graphic means, let’s first look at the words in the phrase: Dialectical + Materialism.

If Marx were to have been extremely weird about language he may more accurately called this theory “How Idealism and Materialism Mutually Influence Each Other To Drive History Forward, With Materialism Being The Dominant Force and Idealism Being Generally Subservient To Materialism.”

Now, what the **** do all those words mean?

If you’re a therapist trained any time after, say, the year 2000, you probably got exposed to the Wise Mind concept: the “dialectical synthesis” (the combination of two opposing things) of Emotion Mind and Reasonable Mind. Marsha Linehan, the creator of Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT), used “dialectics” borrowed mainly from the German philosopher Hegel. Marx, too, was heavily influenced by Hegel.

Hegel was considered an “idealist” in that he believed basically all in existence is a consequence of thoughts and ideas. He’s most famous for the “Hegelian dialectic,” which basically refers to how two opposing ideas smashed together in contradiction create new, better ideas. Black and white together create gray. A thesis and antithesis together create a new thesis, which means we need to be in constant debate about our own ideas to get the best of all ideas, to create the best new ideas which only come from synthesizing the best parts of opposing ideas together.

This conception of dialectics in the West (and elsewhere) became extremely influential and important for centuries.

Excuse Me, I Hate Philosophy, Get To The Fucking Point

You’ve got to remember (unless you never learned this in school, fair) that what gave rise to all the European philosophizing about what a word even is, whether we actually exist, whether there’s a point to anything, was the so-called Enlightenment — late 1600s into the 1700s in Europe. Humans for thousands of years likely wrestled with all kinds of questions, but this was a particularly significant period in history that was shaped by material conditions of the time and various aspects of European and global history that came before.

Previous to this, from the fall of the Roman Empire, the emergence of feudalism into the Dark Ages, everyone was told “do what the priests say the Bible says, and NO you cannot read the Bible yourself.” As this ideological frame of church orthodoxy began to fracture due to material reasons explained below, people frenzied around questions of why — like a child awed in a state of beginner’s mind, drunk on an endless, collectively spreading, manic curiosity about all things.

Big questions emerging at this time were: why people are the way they are, how societies are what they are, why there is freedom and oppression?— really just every big question you can imagine. All over Europe, a dark veil of over one thousand years of insane stupidity was lifted. Everyone became interested in scientific and philosophical inquiry and collectively masturbating together over all these ideas.

Adam Smith, who most of us today think of as the original most hardcore cheerleader for capitalism, and the godfather of modern orthodox economics, published Wealth of Nations in 1776. This work was a direct result of the cultural, ideological shift of the Enlightenment, and it was an attempt to answer the question of why some nations are rich and why some are poor. Much of its popularity in Europe, in Marxian terms, should be attributed to the Superstructural ideology now sweeping the continent due to techtonic shifts in the relations of production within European society’s Base.

Smith basically argues that rich nations are rich because of important choices they make — based on good ideas that come out of those societies. The good things those societies choose to do are:

Increase labor productivity through specialization (some workers just make metal, some just do farming, etc)

People pursuing self-interest (not collective interest) drive the “invisible hand” of the market

Keep government interference with markets at a minimal, so supply and demand do their thing freely (ie, minimal regulation, taxation etc)

Investments in the means of production are important: tools, machinery, infrastructure; these investments increase productivity and wealth

Property rights and rule of law are necessary for stable economic development

Many people don’t know this but Smith actually opposed monopolies and thought rentier capitalism (landlordism) was parasitic; Smith even believed that labor was the source of all wealth in society, which people sometimes attribute to Marx. But Marx looked at Smith’s explanations about why nations were rich or poor, and how capitalism is a superior political-economic system, and he felt there was something hugely missing.

For Marx, Smith’s analysis was too idealist and undialectical.

Smith left out the insane amount of violence necessary for one nation to become able to rob another nation of its resources, land, and labor. It’s not just smart choices, free markets, and labor specialization that makes a nation rich. The richest nations actually need the technology, the military might, the will to do great amounts of violence to other nations in order to turn people into slaves, to force them to plant certain plants and commodify them to then win the global markets (ie, sugar, chocolate, cotton), and to engage in the kind of cruelty required to ignore all the human suffering imposed by these “free market” adventures. But also, the social processes that result in all this violence typically aren’t carried out by everyone in a nation — a ruling class, people who actually have the means to secure more land, more resources, more free or cheap labor, are the ones who compete across nations against each other. The vast majority of people who work for a living, whether unpaid or paid, have virtually no say in anything their ruling class does.

Marx wanted to contend with the highest thinkers of his time, which was in the mid-1800s, by developing a theory that explains why nations are rich and poor based on a radically different vision.

Materialism vs. Idealism

Marx wrestled with two opposing explanations for why everything in society occurs: idealism versus materialism.

Idealism says that everything in society, and matter itself, comes from ideas. Ideas are everything. Big ideas. Big, big ideas that pop into your head somehow. You say them aloud, you discuss and debate them with others. You smash opposite ideas together to create new ideas. Ideas, ideas, ideas. Reality is produced by ideas.

Materialism says that human thought is nearly irrelevant, because material reality is the requirement and basis of all human thought. Human thought only occurs because material reality constructs the human, with the skull, the brain, and the thousands of years of biological history to allow for a “human thought” to occur. Human thought does not create material reality, material reality creates human thought.

The best argument for materialism is to simply point out that a Very Smart Man With A Big Idea can’t utter any thought worth listening to if he’s starved to death, if he has tape covering his mouth, if an army has enslaved him. (And how far will his ideas go if he’s become captured and enslaved, assuming he can even speak the language of his captors?)

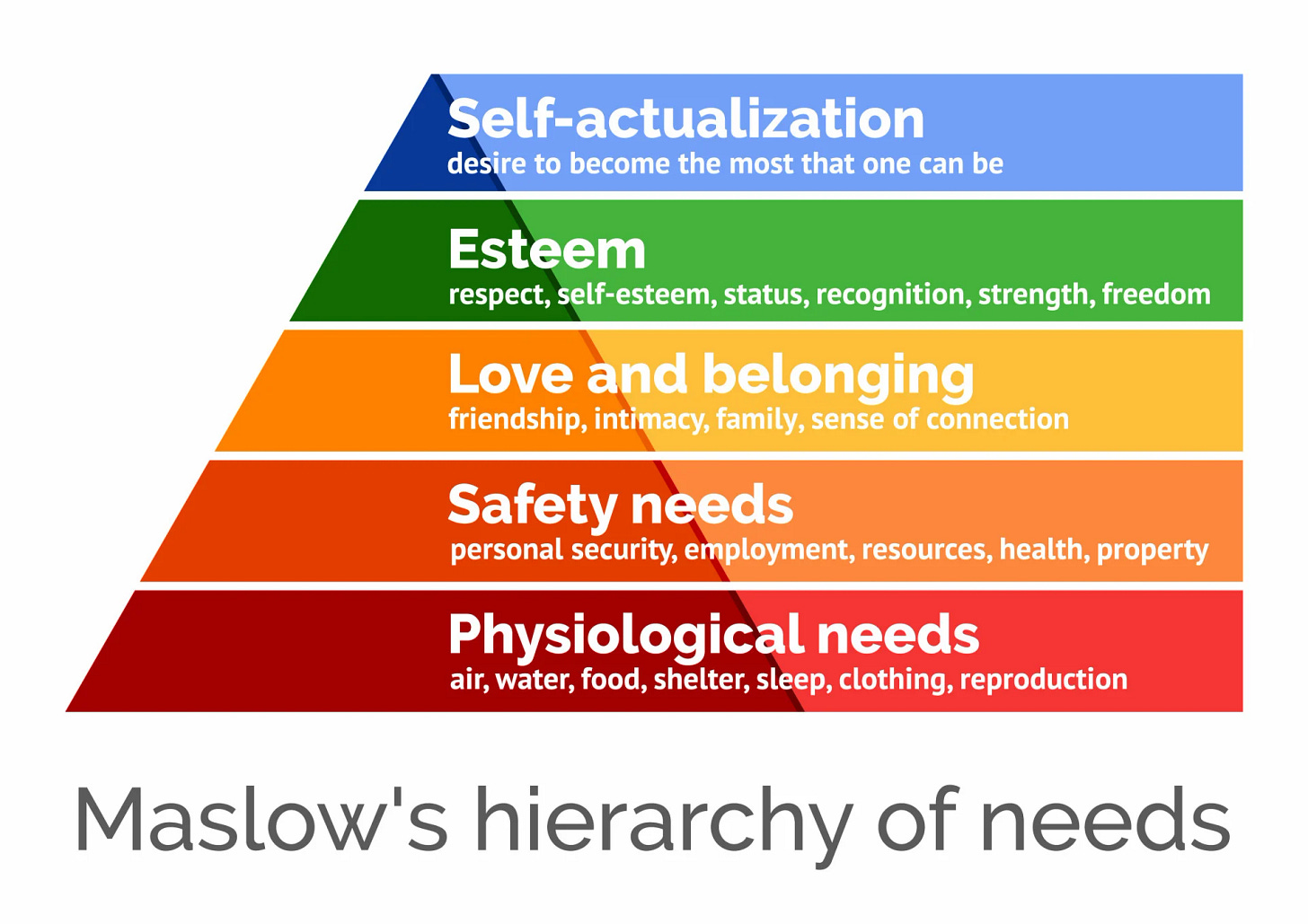

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs explains what I’m saying a bit, but goes nowhere close to where Marx takes these ideas with Dialectical materialism.

The problem with pure materialism is that it can become a form of philosophical determinism which says there is no free will and therefore human beings lack any responsibility to wrestle with morality or make decisions about good or bad choices. Deterministic materialism might argue that all the violence and exploitation of capitalism (and previously feudalism and slavery) is simply a natural consequence of the material foundation of society, and that no human ideas or choices make any kind of difference. This gets us into very dangerous territory, and Marx thought this position was undialectical. Ideas do matter, even if they don’t themselves create material reality.

Marx did something similar to what Linehan did when she created Wise Mind, combining Emotion Mind and Reasonable Mind. She looked at two opposite states of mind and pointed out that if you combine them, you get something better than either one; the resolution of the thesis smashed into its antithesis. That’s Hegel’s dialectical method.

What Marx did in combining materialism and idealism — while claiming that materialism is still a dominant force in shaping and evolving human society — is he created a dialectical synthesis of two very important but ultimately opposing ideas: idealism and materialism.

The Base — relations of production, who owns vs works, etc — is the primary material force constructing and driving society forward through various stages of history. The Superstructure — the ideology constructed out of all the art, culture, religion, philosophy, etc — is the idealism that sits atop the material conditions that make up the foundation of that society. The Base is like the container where all the Superstructure’s ideology lives, and stuff within the Superstructure can shape the Base, but within structural limits.

This was an extremely radical idea in the mid-1800s, and is one that I personally think is repressed in our collective educations in the West generally because of the anti-communist histories of the 1900s. Modern liberalism depends on the idealist idea that all we can do in order to make society better (if that’s even possible) is to fight out ideas in the Superstructure with little to no attention to the Base at all. The Base is assumed to either not matter, or maybe liberals don’t think it exists because we’re all just operating on matter generated from our own ideas in our minds.

How Does All This Connect Back To Historical Materialism?

When we think back through all those stages of history across slavery, feudalism, and capitalism, one relatively stable feature through all of them was and is that there is a relatively small ruling class who owns the means of production. That evolving ruling class ultimately controls society, which might sound like a conspiracy theory to some. But Marx’s claim wasn’t that some evil group of evil people are making evil decisions in secret. It was that the people who control society through all of history, in the waging of wars, construction of prisons, converting humans into slaves, all conquest, all ideological coercion through religion and similar means, is done by those who own the means of production.

They’re not a secret group. They’re always hiding in plain site. The entire working class can always tell who rules them, but due to most working people doing cognitive dissonance by adopting the ruling class ideology, they don’t think there’s anything to be done about the situation. The relations of production simply are what they are.

The Base Is Society’s Entire Foundation

To understand the dominance of the Base with a historical example, think back to feudalism. It’s not a coincidence that in the Superstructure of that society, religious emphasis on peasants needing to “praise the Lord” was central while simultaneously the owners of the means of production were called Feudal Lords. In each mode of production through history it is much more common for ordinary people to glorify the ruling class: the Emperor is great, the King is great, the CEO is great.

To get meta about Marx’s capacity to develop Dialectical Materialism in the mid-1800s, we need to understand the Base and Superstructure of his own society. The European “Enlightenment” of the 1600-1700s was an orgiastic explosion of new ideas about everything. These ideas — occurring in what Marx calls the Superstructure — derived largely from enormous, techtonic shifts in the Base of the European political economy of that time. Namely, the Enlightenment was occurring during the exact (centuries long) moment Europe was transitioning from feudalism to capitalism.

For one of the most riveting deep dives into the microscopic details of this feudalism-to-capitalism transitory period, check out the Hell on Earth podcast by the Chapo Trap House guys:

As I mentioned in Part 3, the merchant class of Europe was steadily gaining power and by sometime between the 1600-1700s, they officially began to become more powerful than the feudal lords. Key changes to the economic Base during this time included changes in the relations of production in several ways. The printing press was invented in 1440, a technological development which on its own had the potential to dramatically change society. New ideas began circulating throughout Europe as this technology was developed and decentralized; something Smith hadn’t considered is that no great idea could really be disseminated without the printing press. And if the church somehow owned the only printing presses in existence (the means of production), only the church could disseminate ideas they wanted circulating in society.

In the year 1517 Martin Luther slammed a fiery set of writings onto the door of a big important German church, basically demanding serious debate and attention to ideas within the Bible. Before and after this event, Luther produced tons of hot content about topics ranging from God, Jesus, the Bible, the Church — some of the biggest ideological concepts of the time. His manic energy and conviction birthed the entire Protestant movement, but while his radical actions had a world changing effect within the European and ultimately global Superstructure, it was only possible because of changes ongoing in the Base.

The printing press was only one of many factors that moved Europe from feudalism to capitalism— all the factors that contributed to this transition were like a cocktail of ingredients that made a giant bomb.

The bubonic plague killed off somewhere around 50% of the entire European population in the 1300s, which created a labor shortage throughout Europe which gave workers more bargaining power. (Whereas the dominant economic form of Europe at this time was feudalism, meaning serfs bound to the land as almost-slaves, serfdom was mainly a rural phenomenon. Cities were developing through Europe and within cities and a lot of the jobs there were more specialized, like artisans, craft-making, etc. Earlier medieval forms of wage labor also became the kindling for the later evolution toward nearly all labor becoming wage-labor once the official transition to capitalism unfolded centuries later.)

The domestic labor shortage coupled with workers being able to demand higher wages pushed the ruling classes of Europe to venture outside of Europe to find cheaper labor — the primary driver of what later became colonialism and imperialism.

All of the above should be understood not just as fascinating history (although it is), and not just that material/physical reality is the “real cause” of important ideas. It’s really just a few examples of how impressive Marx’s theory of Dialectical Materialism is in explaining how happenings within the relations of production (Base) shape ideology (Superstructure).

We can see, too, how the evolution of feudalism to capitalism occurred not primarily because of big, important ideas randomly occurring due to the European Enlightenment, but because aspects of production, labor, relationships between who owns and works, decentralized technological developments spread across the working population, enabled those big important ideas to develop. In other words, Adam Smith couldn’t have produced any interesting ideas about capitalism, wealth, labor, poverty, productivity, supply and demand, if it weren’t for enormous changes in the relations of production throughout Europe. Namely, if the plague didn’t kill half of Europe’s working population, the aristocracy and merchant class never would have had a reason to seek cheaper labor, resources and land from outside its own continent. These events couldn’t have driven the development of capitalist global markets (which utilized slavery and colonialism as forms of early primitive accumulation), and if this never happened, Adam Smith would have had no opinions or ideas to share about why capitalism is a great way to liberate humanity.

You’ll notice by the way this Dialectical Materialist explanation for Europe’s venture into colonialism and imperialism is not idealist in the sense that it doesn’t explain these ventures in terms of Europeans being inherently or accidentally racist, white supremacist and so on. White supremacy as a “system” or ideology did develop over time, and there are debates around how and why this happened, but I personally find the Dialectical Materialist explanation of this development far more compelling than an idealist one. I don’t think humans just randomly have evil thoughts pop into their heads, leading them to join together and consolidate power, to then use that power to construct evil systems of exploitation and oppression. Even in the year 2025 this is probably controversial to say, but I think evil systems today are heavily shaped (and largely caused) by material conditions which primarily live in that Base portion of the Dialectical Materialist equation.

How Does Base ←→ Superstructure Work In Capitalism?

We know in capitalism that the dominant belief system of the Superstructure is about individual responsibility, which gives us the dominant explanation as to why people are poor, or stupid, or sick, or crazy. The default mode of assumption is it’s the fault of the individual that they’re not working hard enough to be housed, get an education, get care from a doctor, find the right medication. There is rigorous debate about this within the capitalist Superstructure, and we’re all aware of liberals and leftists decrying “the system” as moral, evil, ineffective, inhumane. But these ideas floating around within the Superstructure tend not to change the Base, or at least not easily.

The Superstructure Tends To Support, Not Challenge, The Base

The ideology held together within the Superstructure tends to support the Base, not challenge it. The art, music, cultural rituals, messages from the media, the laws, what’s taught in the education system— these things were typically born out of the Base to begin with, and tend never to challenge what’s arranged in that Base. A school teacher during the Roman Empire was not going to teach children about all the cultures and societies destroyed by Rome, how all the slaves were just captives from those destroyed societies, and how what’s really needed to advance society is for all the slaves to unite around a revolutionary program to transform society.

Similarly, the court jester knew he’d be beheaded if he suggested even comically that serfs should form a Pan-European coalition and political party that should use democracy and recruit skilled mercenaries to overthrow feudalism and build economic democracy, and so on. If there are examples of jesters who centered their comedy around this, they were probably executed or punished in some other way very quickly.

In capitalism, do we think that anti-capitalist ideology is generally acceptable within the Superstructure?

Capitalist Realism: when you can “attack” capitalism within the Superstructure because it doesn’t actually change the Base

Now that we have a grasp of the base-superstructure idea, we can see how within capitalism you can ironically “oppose capitalism” from within the Superstructure as long as it doesn’t actually attempt to change the relations of production within the Base. Capitalism can operate in a way where there is freedom of speech, where you can smash just about any idea into any other idea, because the structure of society itself is neither challenged or transformed by this Superstructural process.

You can Tweet whatever you want, yell through the streets running, wear hammer-sickle T-shirts. You can get a tattoo on your face that says “Fuck Capitalism!”

None of these things attempt to change anything in that realm of the relations of production. If 5 guys own all the land, factories, and set all the prices of labor and commodities, they really don’t mind if you complain.

On the other hand, if the masses of working people really wanted for changes in the relations of production to occur, they’d need to have the idea in mind to make that happen. Such a mass of working people would need to then convert this idea into a collective strategy. Ten people wouldn’t do much, 100 wouldn’t do much either. This is why the socialist movement for 150 years has been about “mass politics,” building “mass parties,” and so on. There was an understanding that if capitalism’s structure is such that the ownership class— the 1 percent— basically owns everything, controls everything, then you’d need a working class movement that has a few common features:

1. Organization. The working class would need to be organized into some kind of social set of formations, or a singular formation, to act as one.

A program. This singular organization, or network of organizations, would need some kind of program. We’re for this, and that, and this. These are our aims. We wish to achieve such and such goals. Join us: we’re going to win these goals for ourselves, for the whole working class.

Methods. One mass org or many mass orgs would need to develop effective methods of actually changing the relations of production in the long term. It would need to be understood that random acts of idealistic expression in the Superstructure wouldn’t cut it; moving toward the “workers of the world” owning the “means of production” would require a certain set of methodologies to be effective.

How Do We Change The Base?

If you’re someone who thinks that the “means of production” should be “owned by the workers,” based on what you’ve read in Parts 3 and 4, then you should read on to Part 5 once it’s written. I’m going to give an overview of the methodological approaches to transforming society which various kinds of socialists have developed over the last 150 years. I’m thinking right now that Part 6 will finally return to the question about the psychotherapy group practice — is this a site for socialist activism? Is it not? What should therapists who are moved to identify as socialists actually do with their politics?

Stay tuned!

PS. Remind me to add citations to this one and I will later, feeling lazy.

This post wasn’t just about philosophy. It was about power.

It laid out how most therapists (and honestly, most of us) operate in the Superstructure, the realm of ideas, feelings, beliefs while completely ignoring the Base, which is where the real power lives: who owns what, who controls labor, who benefits from our exhaustion. And it hit hard.

You explained dialectical materialism in a way that made it make sense. I literally use Wise Mind in my day job, and that “emotion mind vs reasonable mind” analogy was the moment the light-bulb went off. You weren’t just nerding out (okay maybe a little), you were showing how systems evolve, and why therapy alone can’t be politically radical if we’re only operating in the realm of individual healing, not collective liberation.

The bit that stayed with me most? That even our anti-capitalist outrage is safe, as long as it stays performative, in the Superstructure. We can wear the T-shirts, write the think-pieces, yell into the void, but unless we’re challenging the Base, nothing actually shifts.

And that stung a little. Because so many of us are doing good work. But if we’re honest? We’re doing it on a system’s terms. And this post made that visible.

So thank you. For the clarity, the fire, the deeply nerdy metaphors that somehow hit harder because they weren’t dressed up. This wasn’t “content.” It was a call to pay attention to where the real levers of change live, and to stop mistaking expression for transformation.

I’ll be rereading this. Probably with snacks.

This is the most interesting discussion of dialectical materialism that I’ve ever read. The context really helps. I think I’ll need to reread it a few times. Thanks for writing this.